|

This is a fascinating article so be sure to click all the links. The History of the Flapper, Part 4: Emboldened by the Bob New short haircuts announced the wearers’ break from tradition and boosted the hairdressing industry (parts 1, 2, 3, & 5 are at the end of this post) On May 1, 1920, the Saturday Evening Post published F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Bernice Bobs Her Hair,” a short story about a sweet yet socially inept young woman who is tricked by her cousin into allowing a barber to lop off her hair. With her new do, she is castigated by everyone: Boys no longer like her, she’s uninvited to a social gathering in her honor, and it’s feared that her haircut will cause a scandal for her family. In the beginning of the 20th century, that’s how serious it was to cut off your locks. At that time, long tresses epitomized a pristine kind of femininity exemplified by the Gibson girl. Hair may have been worn up, but it was always, always long. Part and parcel with the rebellious flapper mentality, the decision to cut it all off was a liberating reaction to that stodgier time, a cosmetic shift toward androgyny that helped define an era. The best-known short haircut style in the 1920s was the bob. It made its first foray into public consciousness in 1915 when the fashion-forward ballroom dancer Irene Castle cut her hair short as a matter of convenience, into what was then referred to as the Castle bob. Early on, when women wanted to emulate that look, they couldn’t just walk into a beauty salon and ask the hairdresser to cut off their hair into that blunt, just-below-the-ears style. Many hairdressers flat out refused to perform the shocking and highly controversial request And some didn’t know how to do it since they’d only ever used their shears on long hair. Instead of being deterred, the flapper waved off those rejections and headed to the barbershop for the do. The barbers complied. Hairdressers, sensing that the trend was there to stay, finally relented. When they began cutting the cropped style, it was a boon to their industry. A 1925 story from the Washington Post headlined “Economic Effects of Bobbing” describes how bobbed hair did wonders for the beauty industry. In 1920, there were 5,000 hairdressing shops in the United States. At the end of 1924, 21,000 shops had been established—and that didn’t account for barbershops, many of which did “a rushing business with bobbing.” As the style gained mass appeal—for instance, it was the standard haircut in the widely distributed Sears mail order catalog during the ’20s—more sophisticated variations developed. The finger wave (S-shaped waves made using fingers and a comb), the Marcel (also wavy, using the newly invented hot curling iron), shingle bob (tapered, and exposing the back of the neck) and Eton crop (the shortest of the bobs and popularized by Josephine Baker) added shape to the blunt cut. Be warned: Some new styles weren’t for the faint of heart. A medical condition, the Shingle Headache, was described as a form of neuralgia caused by the sudden removal of hair from the sensitive nape of the neck, or simply getting your hair cut in a shingle bob. (An expansive photograph collection of bob styles can be found here.) Accessories were designed to complement the bob. The still-popular bobby pin got its name from holding the hairstyle in place. The headband, usually worn over the forehead, added a decorative flourish to the blunt cut. And the cloche, invented by milliner Caroline Reboux in 1908, gained popularity because the close-fitting hat looked so becoming with the style, especially the Eton crop. Although later co-opted by the mainstream to become status quo (along with makeup, underwear and dress, as earlier Threaded posts described), the bob caused heads to turn (pun!) as flappers turned the sporty, cropped look into another playful, gender-bending signature of the Jazz Age. Has there been another drastic hairstyle that’s accomplished the same feat? What if the 1990s equivalent of Irene Castle—Sinead O’Connor and her shaved head—had really taken off? Perhaps a buzz cut would have been the late 20th-century version of the bob and we all would have gotten it, at least once. The History of the Flapper, Part 1:

A Call for Freedom The young, fashionable women of the 1920s define the dress and style of their peers in their own words The History of the Flapper, Part 2: Makeup Makes a Bold Entrance It’s the birth of the modern cosmetics business as young women look for beauty enhancers in a tube or jar The History of the Flapper, Part 3: The Rectangular Silhouette Finally, women could breathe deeply when the waist-nipping corset went out of style The History of the Flapper, Part 5: Who Was Behind the Fashions? Sears styles sprung from the ideas of European artists and couturiers

0 Comments

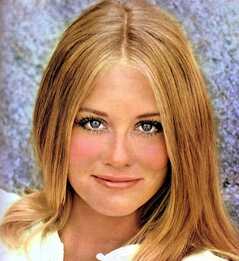

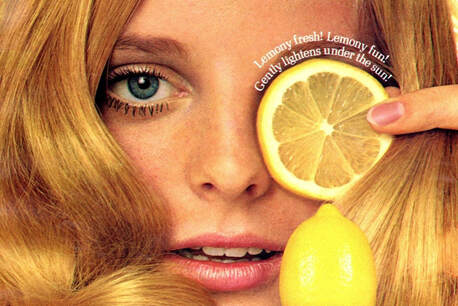

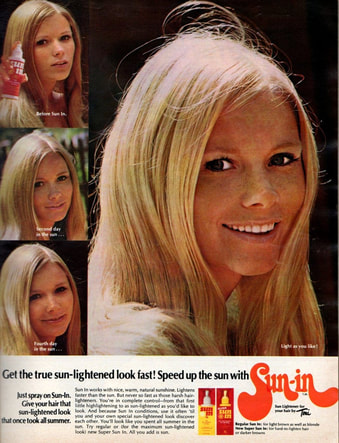

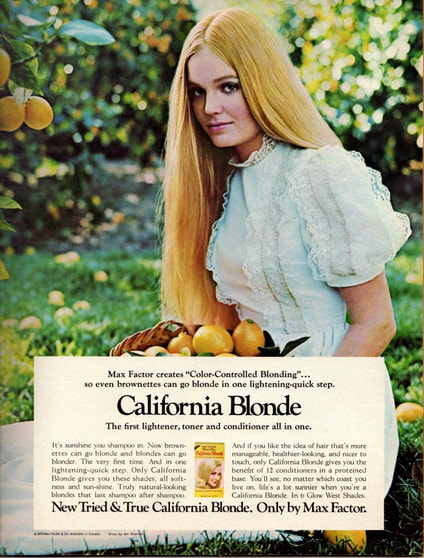

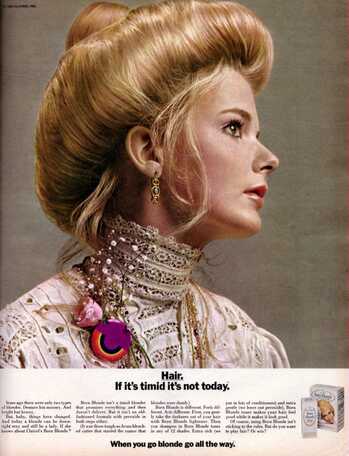

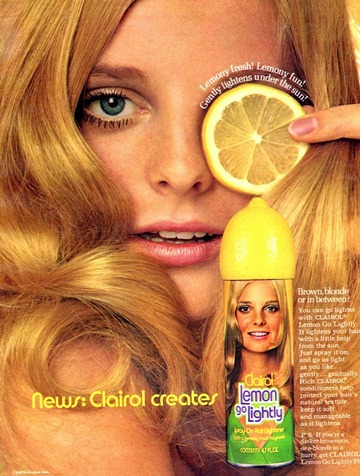

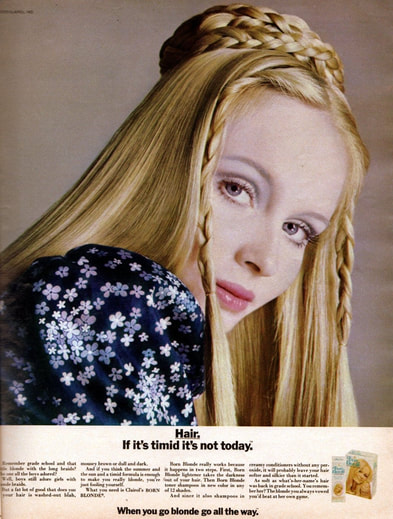

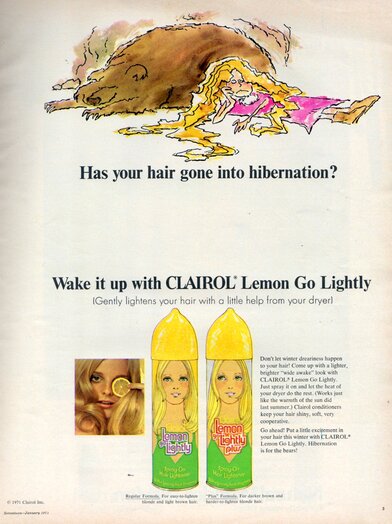

For blonde hair in the ’70s, lemon & sunshine recommended (1977) Asbury Park Press (Asbury Park, New Jersey) April 11, 1977 If you’re a natural blonde, you know you have special problems when it comes to keeping your hair bright and shiny. Now a New York hairstylist has a special tip for blondes who find it hard to keep the “sunshine” in their hair. “Step one,” says Louis of Louis Guy-D, “is to wash the hair often with a gentle shampoo. Naturally blonde hair must be absolutely clean to be its brightest, and this may mean daily shampooing, for which baby shampoo is always recommended. “Blondes can’t go very long between shampoos before dirt and oil turn their hair ‘mousey’ looking. Also, when blonde hair is dry, it can look like straw. Baby shampoo doesn’t strip the hair of all its natural conditioners, which helps blonde hair shimmer with natural highlights.”  Then, to continue the natural approach to bright, shiny blonde hair, Louis suggests a lemon or lime squeeze. “Simply take a lemon or lime and squeeze it onto freshly-washed hair, gently comb through and let dry, preferably in the sun, but a hairdryer will do on rainy days.” Louis says the citrus juices act as a mild bleach and gently lighten the hair. “Continue this treatment for a few days, and any natural blonde will see her hair lighten up, take on shiny highlights and glow just like sunshine,” promises Louis. “By starting this natural highlighting treatment now,” says Louis, “blondes can have sun-lightened hair well before it’s time to slip into that first bikini.” Speed up the sun with Sun-In (1970) Get the true sun-lightened look fast! Just spray on Sun-In. Give your hair that sun-lightened look that once took all summer. Sun In works with nice, warm, natural sunshine. Lightens faster than the sun. But never so fast as those harsh hair-lighteners. You’re in complete control — from that first little highlightening to as sun-lightened as you’d like to look. And because Sun In conditions, use it often ’til you and your own special sun-lightened look discover each other. You’ll look like you spent all summer in the sun. Try regular or (for the maximum sun-lightened look) new Super Sun In. All you add is sun. California Blonde: The first lightener, toner & conditioner all in one. (1970) Max Factor creates “Color-Controlled Blonding”… so even brownettes can go blonde in one lightening-quick step. It’s sunshine you shampoo in. Now brownettes can go blonde and blondes can go blonder. The very first time. And in one lightening-quick step. Only California Blonde gives you these shades, all softness and sunshine. Truly natural-looking blondes that last shampoo after shampoo. And if you like the idea of hair that’s more manageable, healthier-looking, and nicer to touch, only California Blonde gives you the benefit of 12 conditioners in a proteined base. You’ll see, no matter which coast you live on,life’s a lot sunnier when you’re a California Blonde. In 6 Glow West Shades. New Tried & True California Blonde. Only by Max Factor. Clairol’s Born Blonde (1969) Years ago, there were only two types of blondes. Demure but mousey. And bright but brassy. But, baby, things have changed. And today a blonde can be downright sexy and still be a lady. If she knows about Clairol’s Born Blonde. Born Blonde isnt a timid blonde that promises everything and then doesn’t deliver. But it isn’t an old-fashioned formula with peroxide in both steps either. (It was those tough-as-brass bleached cuties that started the rumor that blondes were dumb.) Born Blonde is different. Feels different. Acts different. First, you gently take the darkness out of your hair with Born Blonde lightener. Then you shampoo in Born Blonde toner in any of 12 shades. Extra rich (we put in lots of conditioners) and extra gentle (we leave out peroxide), Born Blonde toner makes your hair feel good while it makes it look good. Of course, using Born Blonde isn’t sticking to the rules. But do you want to play fair? Or win? When you go blonde, go all the way Lemony fresh! Lemony fun! (1970) Lemon Go Lightly – Gently lightens under the sun! Brown, blonde or in between? You can go lighter with CLAIROL Lemon Go Lightly. It lightens your hair with a little helpfrom the sun. Just spray it on, and go as light as you like… gently … gradually. Rich CLAIROL conditioners help protect your hair’s natural texture. keep it soft and manageable as it lightens. P.S. If you’re a darker brownette, or a blonde in a hurry, get CLAIROL Lemon Go Lightly Plus. Hair. If it’s timid it’s not today (1970) Remember grade school and that little blonde with the long braids? The one all the boys adored? Well, boys still adore girls with blonde braids. But a fat lot of good that does you if your hair is washed-out blah mousey brown or dull and dark. And if you think summer and the sun and a timid formula is enough to make you really blonde, you’re just fooling yourself. What you need is Clairol’s Born Blonde. Lemon Go Lightly (1971) Has your hair gone into hibernation?

Brown, blonde or in between? You can go lighter with CLAIROL Lemon Go Lightly. It lightens your hair with a little help from the sun. Just spray it on, and go as light as you like… gently … gradually. Rich CLAIROL. conditioners help protect your hair’s natural texture. keep it soft and manageable as it lightens. P.S. If you’re a darker brownette, or a blonde in a hurry, get CLAIROL Lemon Go Lightly Plus. For nearly two centuries, powdered wigs—called perukes—were all the rage. The chic hairpiece would have never become popular, however, if it hadn't been for a venereal disease, a pair of self-conscious kings, and poor hair hygiene. The peruke’s story begins like many others—with syphilis. By 1580, the STD had become the worst epidemic to strike Europe since the Black Death. According to William Clowes, an “infinite multitude” of syphilis patients clogged London’s hospitals, and more filtered in each day. Without antibiotics, victims faced the full brunt of the disease: open sores, nasty rashes, blindness, dementia, and patchy hair loss. Baldness swept the land. At the time, hair loss was a one-way ticket to public embarrassment. Long hair was a trendy status symbol, and a bald dome could stain any reputation. When Samuel Pepys’s brother acquired syphilis, the diarist wrote, “If [my brother] lives, he will not be able to show his head—which will be a very great shame to me.” Hair was that big of a deal. Cover-Up And so, the syphilis outbreak sparked a surge in wigmaking. Victims hid their baldness, as well as the bloody sores that scoured their faces, with wigs made of horse, goat, or human hair. Perukes were also coated with powder—scented with lavender or orange—to hide any funky aromas. Although common, wigs were not exactly stylish. They were just a shameful necessity. That changed in 1655, when the King of France started losing his hair. Louis XIV was only 17 when his mop started thinning. Worried that baldness would hurt his reputation, Louis hired 48 wigmakers to save his image. Five years later, the King of England—Louis’s cousin, Charles II—did the same thing when his hair started to gray (both men likely had syphilis). Courtiers and other aristocrats immediately copied the two kings. They sported wigs, and the style trickled down to the upper-middle class. Europe’s newest fad was born. The cost of wigs increased, and perukes became a scheme for flaunting wealth. An everyday wig cost about 25 shillings—a week’s pay for a common Londoner. The bill for large, elaborate perukes ballooned to as high as 800 shillings. The word “bigwig” was coined to describe snobs who could afford big, poufy perukes. When Louis and Charles died, wigs stayed around. Perukes remained popular because they were so practical. At the time, head lice were everywhere, and nitpicking was painful and time-consuming. Wigs, however, curbed the problem. Lice stopped infesting people’s hair—which had to be shaved for the peruke to fit—and camped out on wigs instead. Delousing a wig was much easier than delousing a head of hair: you’d send the dirty headpiece to a wigmaker, who would boil the wig and remove the nits. Wig Out By the late 18th century, the trend was dying out. French citizens ousted the peruke during the Revolution, and Brits stopped wearing wigs after William Pitt levied a tax on hair powder in 1795. Short, natural hair became the new craze, and it would stay that way for another two centuries or so. from MentalFloss For a deeper dive into hair powder and "big wigs" check out this article: Hairdressers curling one person and using hair powder on another.

By Charles Catton in 1780s. Public domain. Per the Oxford English Dictionary, "bangs" as a term for the fringe of hair lying over the forehead originated in the stables. Horses' tails were sometimes allowed to grow to a certain length, and then were cut off in an even, horizontal trim called a "bangtail." Racehorses were sometimes called bangtails. And Green's Dictionary of Slang suggests "bangtail" actually originated in Scotland, not the US. "Bangtail" was first applied to human hairstyles as early as 1844, but the OED cites the first use of "bang" as 1878. "Bang" meaning "abrupt or sudden" has been used in English since the late 18th century; more details here at Grammarphobia: Q: Why does the word “bangs” refer to a fringe of hair cut straight across the forehead? A: The use of “bangs” (or “bang”) for that short fringe of hair originated in the US in the 19th century, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. But the usage has its roots in “bangtail,” an equine term seen on both sides of the Atlantic. So let’s start our investigation in the stables. The word “bangtail” is defined in the OED as “a (horse’s) tail, of which the hair is allowed to grow to a considerable length and then cut horizontally across so as to form a flat even tassel-like end.” The dictionary notes that the term has also been used in Australia for cattle with tails cut that way, and in the US as slang for a horse, especially a race horse. The earliest citation for “bangtail” in Green’s Dictionary of Slang is from a Scottish journal, suggesting that the term may have first reared its head in the British Isles. Green’s cites an 1812 issue of the Edinburgh Review that mentions a stud horse named Bangtail, but the name surely came from an even earlier use of the term. Through a Google search we found a comic British story about fox-hunting, published in 1851, in which “bang-tail” appears least seven times in reference to tails as well as horses. The story, “Turning Out a Bagman,” by a writer signed “B.P.W.,” is about two London greenhorns who are on vacation and want to hire a pair of hunters. The showily groomed horses they hire are called “bang-tails,” and are described as having “such flowing bang-tails as at once stamped them in the eyes of our friends as ‘out-and-out’ thorough-breds.” The story is chockfull of slang (like “bagman” to mean “fox”), which may explain the repeated use of “bang-tail” instead of “horse.” Apparently it didn’t take long for “bang” to graduate from horse tails to human hair. We found an 1844 travel book, Revelations of Russia by Charles Frederick Henningsen, that mentions a man’s hair cut “somewhat in the fashion of a thorough-bred’s ‘bang-tail.’ ” In another travel book we came across an 1849 entry that describes a woman whose hair was braided in back and “cut in bang style” in front. The OED’s earliest citation for the human usage is from a letter written in 1878 by Frances M. A. Roe, author of Army Letters From an Officer’s Wife: “It had a heavy bang of fiery red hair.” (The “bang” was on a face mask in a shop window in Helena, in the Montana Territory.) Another American, William Dean Howells, also used the word in his book The Undiscovered Country (1880): “His hair cut in front like a young lady’s bang.” A Google search turned up a plural reference in an 1883 article from the New York Times. A Catholic priest, lecturing Sunday school children, “condemned the fashion of wearing ‘bangs’ in severe terms.” A matching adjective (as in “banged” hair) and verb (to “bang” or cut the front hair straight across) also emerged in the 1880s, according to citations in the OED. Here are a couple of examples: “He was bareheaded, his hair banged even with his eyebrows in front” (from the Century Magazine, 1882), and “They wear their … hair ‘banged’ low over their foreheads” (from Harper’s Magazine, 1883). So it would appear that the verb “bang” (to cut hair straight across) emerged after the hairstyle and not before, unless there are earlier verb references we haven’t found. That still leaves us with a question: Why did “bang” mean bluntly cut? Both Green’s and the OED indicate that since the late 1500s the verb “bang” has meant to hit or thump, and the noun “bang” has meant a blow or a thump. And “bang” has been used adverbially since the late 18th century, the OED says, to mean “all of a sudden,” or “suddenly and abruptly, all at once, as in ‘to cut a thing bang off.’ ” Since the bangs on a person’s forehead, like a horse’s banged tail, end abruptly—you might say with a “bang!”—perhaps the word is simply a case of creative English. A collection of humor pieces, Wit and Humor of the Age (1883), takes the creativity a step further. In a story by Melville D. Landon, one chambermaid asks another “if she banged her hair.” “Yes, Mary,” the first chambermaid says. “I bang my hair—keep a banging it, but it don’t stay bung!” A Short, Uneven History of Bangs From Cleopatra to Kate Moss, a journey through some of history's greatest bangs. Bangs are great. They can change your look aggressively with relatively little work, hide a fivehead, and let your ex know via Instagram that you are completely over them and, actually, making a lot of fun new choices as a single person, for reference please see: bangs. But with bangs as with banging, there are hundreds of ways to do it. Join us on a journey through the history of the "French facelift." 30 B.C.E.: Not to start off on a total bummer, but Cleopatra's famously blunt bangs are a myth. In actuality, she would have worn a wig of tight curls over a shaved head, as was the fashion at the time. The popular image of Cleopatra with bangs comes from the 1934 film Cleopatra, which made use of actress Claudette Colbert's pre-existing bangs. 1200s: Women's hair was mostly hidden under hats or tightly braided during the medieval period, but what is a wimple if not fabric bangs? 1800s: The regency period brought tightly curled, forehead-framing tendrils into fashion—not quite bangs exactly, but the early cousin of the limp tendril situation that swept proms in the mid-90s. 1910s: The turn of the century saw the Gibson Girl's pouf-y updos loosened and swept forward in parted bangs that look like the brushed out relative of regency ringlets. 1920s: The twenties were when bangs really got going. Women were officially experimenting with all kinds of looks—dark lipstick, shorter dresses, riding bicycles, can you imagine—and their hair was getting wild too. The most famous bangs of the period are the blunt, fringed cuts of flappers like Louise Brooks, but Josephine Baker's curled, slicked down fringe was an ahead-of-its-time take on the kind of swooped bangs that would come into popularity in the 30s and 40s. 1940s: Hair was generally kept off the face in the 40s, but dramatically so. Unwanted forehead hair was combed up into poufs and pompadours, or teased into "bumper bangs" which were suspended in the air above the forehead and often embellished with hats, pins or flowers. (If you were a teen with any interest at all in the ukulele, you have at one point attempted this kind of bang.) A sultry alternative was a Veronica Lake-style "peekaboo bang," a long, sideswept section of hair brushed over part of the face—very Jessica Rabbit, very inconvenient. 1950s: This decade was all about what's now known as baby bangs: Audrey Hepburn with her short, wispy, impulse fringe in Roman Holiday; Natalie Wood's child-like pageboy cut with gamine bangs, a throwback to her child star days with her trademark bangs and braids. But the most famous bangs of the period belong to Bettie Page, whose short, rounded pinup fringe is probably, I'm calling it here, the most influential set of bangs of all time? Page, whose mother was a hairdresser and who often did her own hair and makeup on pinup shoots, initially cut the bangs to minimize a high forehead but allow for light on her face in photographs. To date baby bangs have been associated with the riot grrrl movement, "rockabillies," and Beyonce's first-ever (only?) aesthetic mistake. 1960s: Bangs in the sixties were still fairly short, though generally sideswept and sprayed into place beneath beehives and other Aquanet-assisted updos. The end of this decade saw the pixie cut + barely-there bangs combo that became legendary as the reason Frank Sinatra left Mia Farrow. (She has corrected this rumour: she had cut her own mini-fringe and short crop earlier that year, and Sinatra loved it.) 1970s: The aesthetic was very long, loose, and flowing in the 70s, and bangs were no exception. Jane Birkin's delicate, piece-y fringe was just as iconic as the Hermés bag she inspired (and recently rejected). Farrah Fawcett's feathered hair was a high-volume approach to bangs that carried into the 80s, hard. 1980s: Bangs got bigger and weirder in the 80s. As feathered, brushed out bangs gave way to the Statement Bang, fringes were hairsprayed up and out into improbable hair-hats, or permed into oblivion a la Sarah Jessica Parker. Hair metal bands got men in on the bangs situation in an unprecedented way: 80s Bon Jovi and present-day me have the same haircut. 1990s: The 90s were a great time for weird girl bangs, with goth V and rounded Spock options popular among vampire chicks and vintage babes, respectively. Uma Thurman rocked some impressively blunt bangs to dance and do drugs and almost die in Pulp Fiction, and shiny, curled-under bangs worked with Drew Barrymore's girlish curls. But this was also the decade that gave us the Rachel, and with it, the sidebang. In the layering frenzy of the 90s a bang-like layer of swooped, face-framing hair was mandatory, leading to the aforementioned formal tendril situation: two perfect bits of hair, pulled out of an otherwise intense updo, lying limply on either side of the face. 2000s: The sidebang continued its terrible reign until Zooey Deschanel started a full, retro-bangs trend that hit pensive girls with poetry ambitions particularly hard and never looked back, becoming a shorthand for a particular kind of whimsical indie lady who owned vintage teacups and loved collage. In 2007 Kate Moss got blunt, thick, straight-across bangs and they became fully, properly cool. It is a scientific fact that between 2008 and 2009, 100% of women were at the very least considering getting bangs. 2010s: The heady days of the late aughts bang explosion are over. Bangs are being grown out right now, with the favoured hair a sort of middle parted, two days after a wash, slightly tousled that The Cut is calling "rich girl hair." However, just as ubiquitous is the "lobb" ("long bob," get it), a blunt, shoulder-length cut that often comes with bangs. (Think Taylor Swift, Emma Stone, and other small white celebrities.) It's a beautiful time to be thinking about bangs: they are so ubiquitous that they'll never be out of style, no matter what weird thing you try! Dry shampoo has solved the clean hair, greasy bangs dilemma! You can buy clip in bangs that just snap into your head and come off whenever you want! They're still the most fun you can have with scissors in a bathroom and a glass of wine! With every of bangs from history on offer, you just have to decide what kind of girl you want to be.

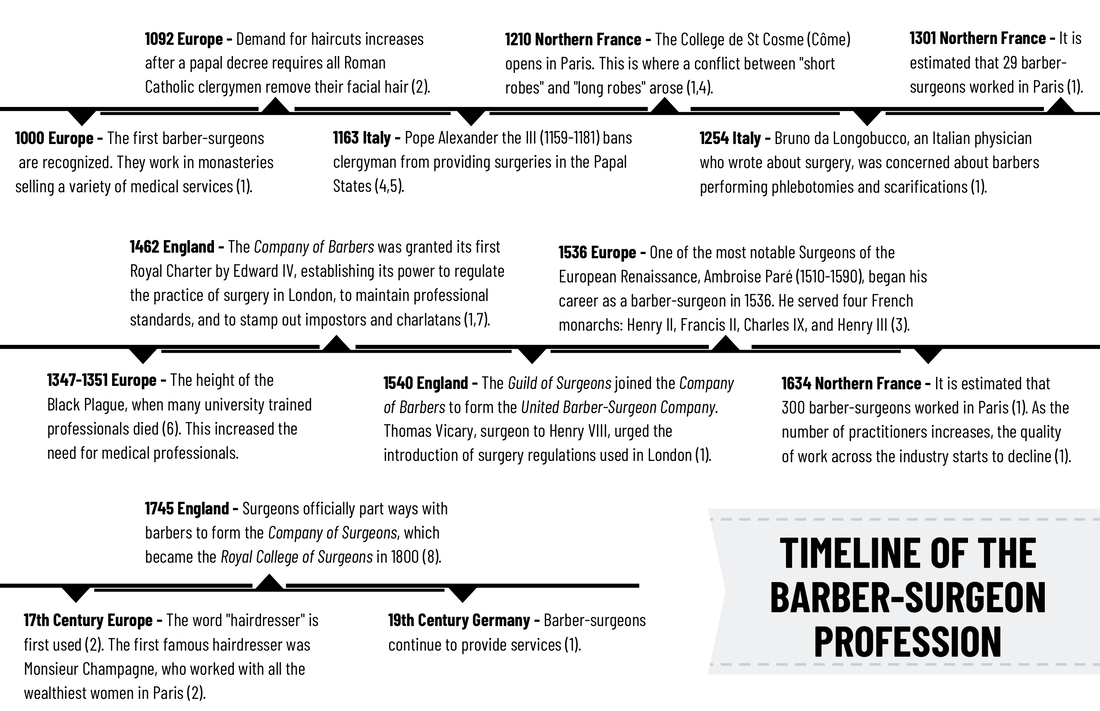

Barbering is one of the oldest professions in history, and there is more to its story than cutting hair alone. I became interested in this topic after reading an article published by the History Channel titled "Why are barber poles red, white and blue?". The article shares that "barber pole’s colors are a legacy of a long-gone era when people went to barbers not just for a haircut or shave but also for bloodletting and other medical procedures". On the pole, the red represented blood, the white bandages, and the blue veins. According to the Encyclopedia of Medical History by Roderick E. McGrew, barbers who offered medical services were referred to as "barber-surgeons", and along with trimming hair they also "bled, cupped, leeched, gave enemas [and] pulled teeth". These procedures were recognized by physicians during the Middle Ages, but deemed too menial for doctors to perform. This led to monks, who often cared for the sick at monasteries, to start conducting surgical procedures. Barbers frequently worked at monasteries because Roman Catholic clergymen were required to remove their facial hair per a papal decree in 1092 (2). Monks would borrow the barbers' sharp instruments, which eventually led to barbers offering surgical services themselves (2). As you can imagine, this raised many questions about who was qualified to provide medical procedures. Should only university trained professionals facilitate them? Was apprenticeship training enough? Should one person be allowed to cut hair, conduct dental work and perform surgery? The debate unfolded in different ways across Europe. Southern France, Spain and Italy In these regions, barber-surgeons saw their status constantly fluctuate from revered “knowledge healer” to “medical conman”. Their relevance to healthcare didn't receive much recognition because medicine and surgery were never treated as separate professions. In 1254, Bruno da Longobucco, an Italian physician who wrote on surgery, complained about barbers performing phlebotomies and scarifications (1). It was the first public sign of physicians' dissent towards other professions encroaching on the market for medical services. Northern France Demand for surgical services in this region became so high that it required an abundance of surgeons to meet it (1). Barber-surgeons were able to respond to the demand faster than university graduates because they had no formal certification process in place before entering the field. Many physicians felt the skill and training required to practice medicine was threatened by the number of barber-surgeons performing surgeries, so some medical facilities started banning operations to distinguish doctors from surgeons (1). Despite this, France legitimized the barber-surgeon field by establishing the College de St Cosme (Côme) in 1210, which taught both physicians and surgeons in Paris. However, on campus there was still an issue of class between the faculty teaching each subject. Professors who wore long-robes were physicians entitled to conduct surgeries, while those who wore short robes still needed to pass certain exams and apprenticeship hours to do so. In quiet rebellion, the short robed faculty members partnered with barber-surgeons outside of the college, and began teaching them anatomy lessons in exchange for their sworn allegiance to the short robed division of the school. In 1499, barber-surgeons sought more autonomy, mainly in the form of demonstrations via their own cadavers (1). A power struggle ensued, with the short robed division of the college withdrawing their support. The short robed faculty eventually acquiesced to the long robed faculty in 1660, essentially acknowledging physicians' superiority over the surgical profession at the time. Outside of universities, the number of barber-surgeons continued to rise, but the quality of their services deteriorated without access to proper schooling (1). England Similar to France, physicians in England initially disliked surgeries. A surgeons guild was created in 1368 that joined forces with physicians in 1421 (1). Despite this, the Guild of the Barbers of London received a charter from Edward the IV himself in 1462. This likely elevated the barber-surgeon's class and seniority enough to influence a future partnership between the Guild of Surgeons and the Company of Barbers in 1540, which together became the United Barber-Surgeon Company (1). This organization lasted for over two centuries, until 1745, when England also saw barbers and surgeons part ways as the need for university education in medicine gained social approval. At this time surgeons formed the Royal College of Surgeons, which is still operating today (8). Check out the timeline below to see how the barber-surgeon profession evolved into the 18th century. Timeline Sources (1) 'Encyclopedia of Medical History' (1985) Internet Archive. Available at: https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofme1985mcgr/page/30/mode/2up (Accessed: 6 October 2020). (2) ‘Hairdresser’ (2011) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hairdresser (Accessed: 6 October 2020). (3) ‘Ambroise Paré’ (2020) Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ambroise-Pare (Accessed: 6 October 2020). (4) ‘Barber surgeon’ (2011) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barber_surgeon (Accessed: 6 October 2020). (5) Nix, E. (2018). ‘Why are barber poles red, white and blue?’, History Stories, 22 August. Available at: https://www.history.com/news/why-are-barber-poles-red-white-and-blue (Accessed: 6 October 2020). (6) ‘Black Death’ (2020) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Death (Accessed: 6 October 2020). (7) 'History of the Company' (2014) The Worshipful Company of Barbers. Available at: https://barberscompany.org/history-of-the-company/ (Accessed: 6 October 2020). (8) ‘Royal College of Surgeons of England’ (2020) Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Royal_College_of_Surgeons_of_England&action=history (Accessed: 7 October 2020). This bit of Hair History was found at the Hairlooks Blog

|

Hair by BrianMy name is Brian and I help people confidently take on the world. CategoriesAll Advice Announcement Awards Balayage Barbering Beach Waves Beauty News Book Now Brazilian Treatment Clients Cool Facts COVID 19 Health COVID 19 Update Curlies EGift Card Films Follically Challenged Gossip Grooming Hair Care Haircolor Haircut Hair Facts Hair History Hair Loss Hair Styling Hair Tips Hair Tools Health Health And Safety Healthy Hair Highlights Holidays Humor Mens Hair Men's Long Hair Newsletter Ombre Policies Procedures Press Release Previous Blog Privacy Policy Product Knowledge Product Reviews Promotions Read Your Labels Recommendations Reviews Scalp Health Science Services Smoothing Treatments Social Media Summer Hair Tips Textured Hair Thinning Hair Travel Tips Trending Wellness Womens Hair Archives

June 2025

|

|

Hey...

Your Mom Called! Book today! |

Sunday: 11am-5pm

Monday: 11am-6pm Tuesday: 10am - 6pm Wednesday: 10am - 6pm Thursday: By Appointment Friday: By Appointment Saturday: By Appointment |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed